Arturo Martini

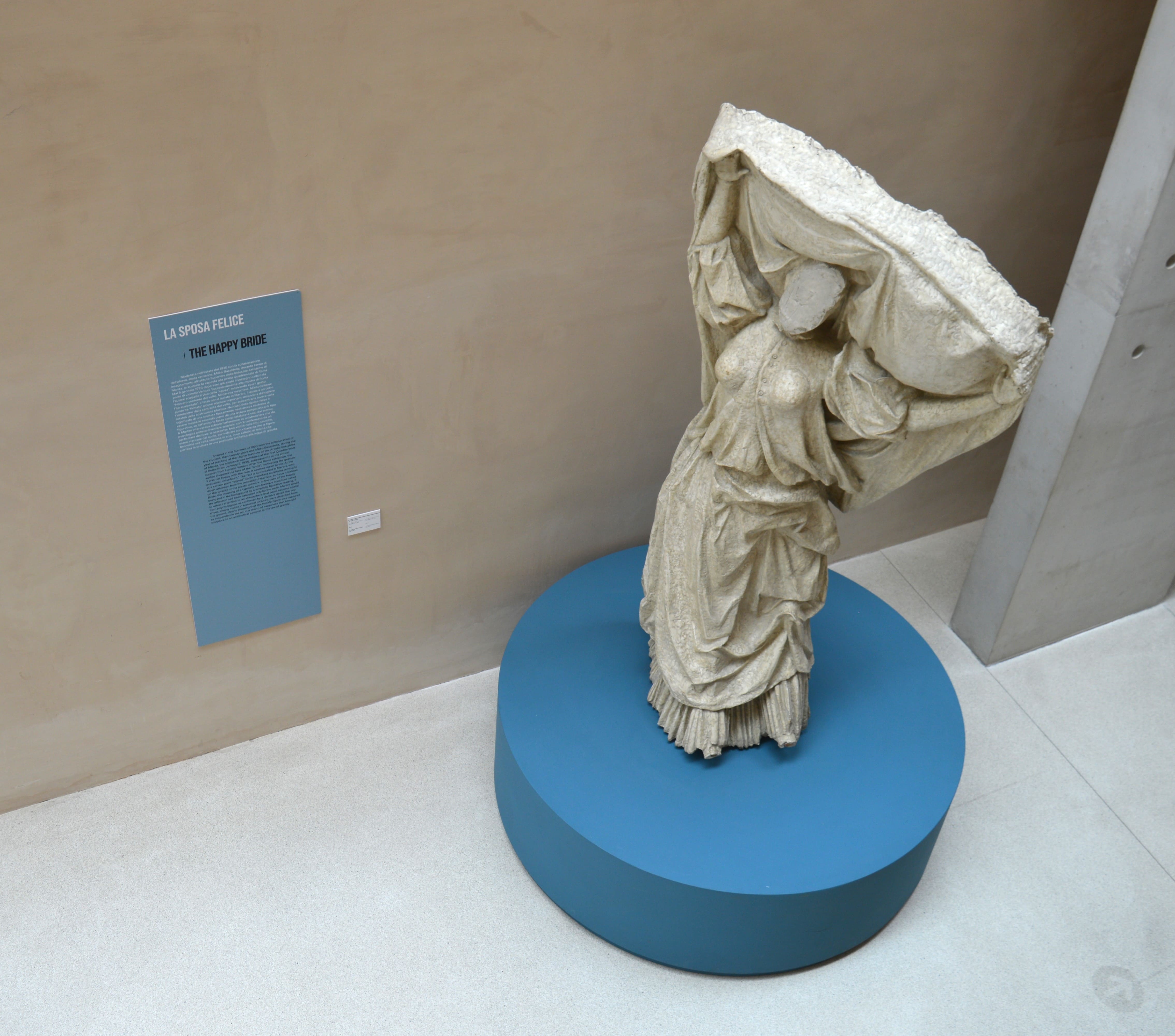

Arturo Martini was born in Treviso in 1889. His work as an artist is very important for the history of modern sculpture. Thanks to gifts and purchases, the Bailo Museum preserves many of his works, both from his youth and his maturity.

In Treviso, where he lived until 1920, Martini received his first teachings from the sculptor Antonio Carlini and participated at the Trevigiana Art Exhibition.

In 1909 he made a long stay in Munich: thanks to this experience and the stimuli he received in the German city, he developed a series of original models for the Gregorj ceramic furnace in Treviso and had new ideas for his sculptures.

In Venice, he participated in the collective exhibition of the Bevilacqua La Masa Foundation, an institution that aimed to help young artists. He became friends with the painter Gino Rossi, with whom he traveled to Paris and shared the desire to change the rules of painting and sculpture and do something new compared to tradition.

After the war, he returned to representing the human figure. He often stayed in Rome and studied ancient Roman and Etruscan models: among the masterpieces of this period we can remember the sleeping figure of Pisana.

The possibility of using the large oven of the I.L.V.A. factory in Vado Ligure allowed him to create an important series of large terracottas, such as Venus of the ports, for which he received prizes and awards.

During the Second World War, he was called to teach sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, of which he became director in 1944. In these years he reflected deeply on his work and on the possibilities of development of modern sculpture.

He died in Milan a few years later, in 1947.